In Between History

Sep 12 - Dec 12, 2014

Kenderdine Art Gallery

“To set aside the sympathy we extend to others beset by war and murderous politics for a reflection on how our privileges are located on the same map as their suffering, and may –in ways we might prefer not to imagine –be linked to their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others, is a task for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark.”[1]

– Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others

In between History presents key contemporary pieces from the University of Saskatchewan permanent art collection. This exhibition contemplates the gaps and absences in history, residing on the instability of what is considered “truth.” The artists offer counter-narratives to historical atrocities, social and political unrest, anxiety, power and disillusionment. The dialogue between the works has been arrived at by unpacking their mutual investigations into alternative modes of understanding history and cultural memory.

Tony Scherman explores the subconscious in his paintings and drawings, depicting everyday objects that are imbued by “unthinkable thoughts” to conceptualize the life of dictators such as Hitler and Napoleon. “Scherman’s interest in painting the mythic subject of – the demons or heroes of history - is the possibility of demythologizing them, which in turn, is another form of taboo.” For example, in Scherman’s portrait of Hitler’s dog, Blondie, he aims to destabilize sentiment. “If we love dogs, we are sharing a common thought with a demon.”

Scherman’s food-subject works takes reference from particular historical meals that took place. For example the entire series, “Luch at Wannsee, is a reference to the Nazi conference held at Wannsee, near Berlin on 20 January 1942. The horrible absurdity is that a light lunch was served while the “Final Solution” for the extermination of Jew in Europe was formulated.” Scherman is not providing facts or documentation of such events for the viewer, he positis, “it is painting, not history, so I can lie in order to reveal the truth.”

In the photo drawing, La Fenetre,Versailles, Vikky Alexander calls into question the famous utopian garden of Versailles, France. Alexander is “fascinated by spaces that are saturated with extreme beauty and total artifice,” and how these images function as escapism or disembodiment from the everyday.[2]

“Salloum's series of projects addressing social and political realities and representations, manifestations, and enunciations, focusing on borders / nationalisms / movements (shifts, transitions, and interstitial space/time) and subjectivity and the conditions of living between polarities of culture, geography, history, and ideology.”[3]

Angela Grossman’s work explores the socially marginalized, focusing on vulnerability and power of the female, particularly that of young adolescent females. Her work collages found photographs with drawing, painting and magazine cut-outs. Grossmann’s haunting images reveal traces from her family history, her father was German Jew and lived during the Second World War. “Though she “used to cringe” when the death of her father’s family in the Holocaust was mentioned in regard to her work, she has come to accept it, and it may be this proximity to injustice that inflames Grossmann’s interest in the marginalized.”

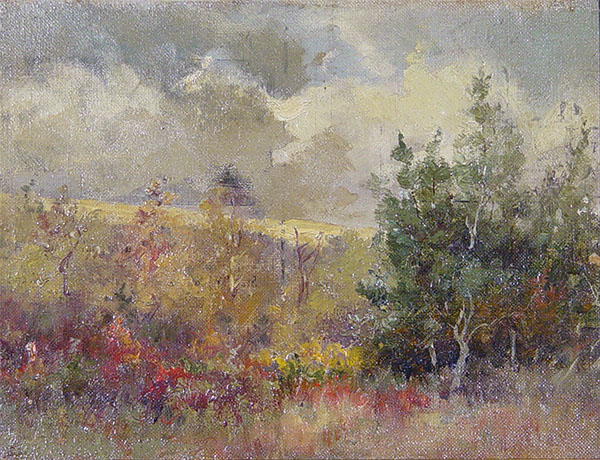

Paul Fornier’s haunting painting, Loomings was created over a three-year period, the work mines through the unspeakable tragedy of the holocaust. Originally titled, Echoes in the Camp, “The work was conceived as a memorial to the holocaust, evident by the notations by the artist on the back of the canvas. (Scrawled into the paint on the surface of the canvas itself is the work “BlockiHesta,” a slang term used in the camps for cell block).”

From the series, Some places in the world a woman could walk, Allyson Clay’s piece references feminist theory through her anthropological pairing of photo and text. Clay is purposing a female flaneur, riddled with domestic boredom and the complexities of the ever-increasing urban survielence on everyday activities. Clay creates a triangulation by placing in the gallery viewer in the position of the voyeur, further problematizing the distinctions of public and private, and the politics of the gaze.

Mary Longman’s Hills Never Die, is a lenticular photograph that melds an original archival photograph from 1885 by O.B Buell, with a photograph of the artist from 2009, standing in the exact same location in Labret, Fort Qu’Appelle. Longman’s research into the photograph revealed that “the unidentified Cree man bore a striking resemblance to Chief Big Bear (1825-1888) and I suspected that the photograph was take just before the Frog Lake resistance on April 2, 1885, or within Big Bear’s last month of freedom before he surrendered on July 2, 1885.” Longman work addresses colonialism and the historical absences in the documenting of Metis history, she posits, “the landscape holds the history, a picture is worth a thousand words and the hills never lie.”

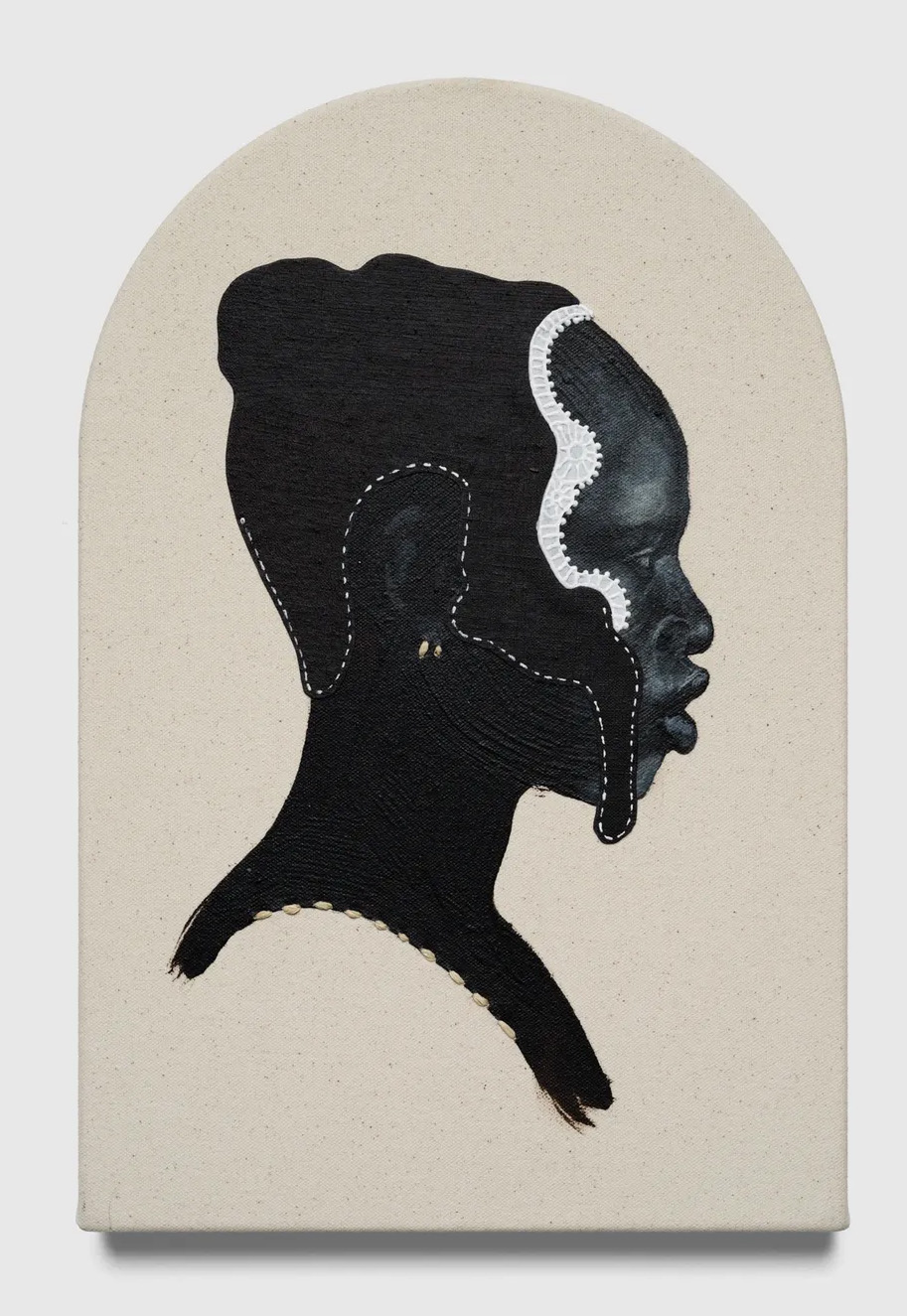

In Louise Noguchi's Compilation Portrait, the artist weaves strips of large scale, self-portrait photographs with photographs of murderer. This mingling of individual identity denies ready distinctions between innocence and culpability, and implies that the capacity to commit a crime lies within each of us. Blurring the lines of identity, race, gender and the innocent with the criminal, Noguchi raises questions surrounding societies subjection to these images and their historical recordings.

Douglas Walker combines industrial architecture, physics and archives through a photographic process called process called cliché-verre. His haunting images of discarded rocket boosters, a wind tunnel, a refinery, and a locomotive, speak to the post-industrial age, emphasizing the history of production and distribution of objects.

Chris Cran’s silkscreened portrait from a the series “The Heads,” utilizes the half-tone dot pattern to “give anonymous individuals from the 1950s and 60s pulp magazine their 15 minutes of fame.” Cran is interested in our need to place these faces by associating them to famous individuals (such as Patsy Cline) in order to validate them with a sense of familiarity. “The desire to do so exists because we are constantly caught slipping into the gaps between what is present and what is absent.”

[1] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, p.102-103, 1993, Picador, New York

[2] Vikky Alexander, “Vaux-le-Vicomte Panorama.” Essay by Ian Wallace, p. 19.

[3] Jayce Salloum (everything and nothing), http://www.16beavergroup.org/singapore/#jayce