The Sitter

September 4 - December 19, 2009

Kenderdine Art Gallery

Leah Taylor, exhibition curator

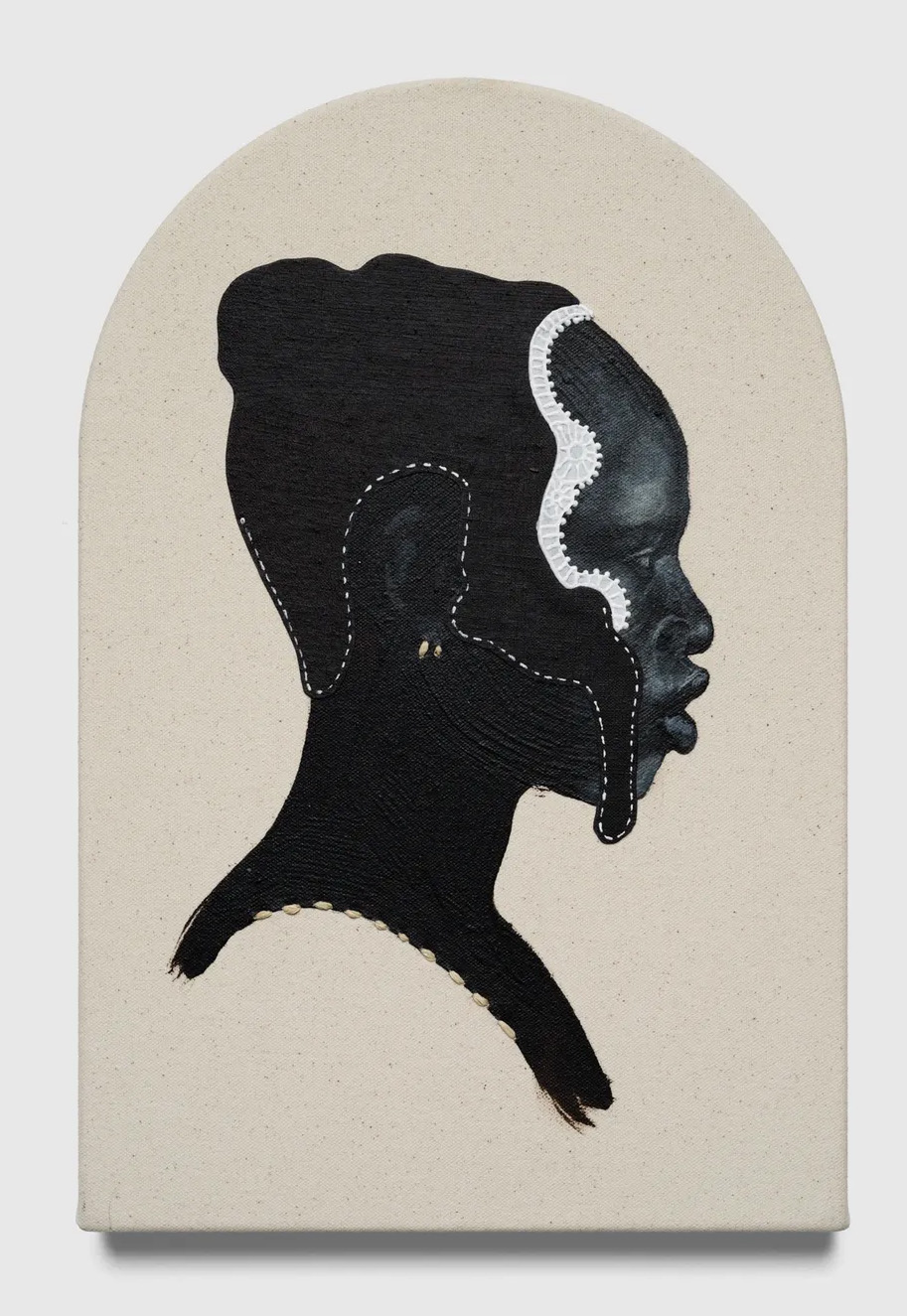

As the subject of portrait photography, “the sitter” plays several roles in the history of the medium. The sitter becomes a means to document the development of photographic techniques, and represents the transition of the photographer from document-maker to artist. Most significantly, the sitter is a symbol for social, political and economic commentaries.

The viewer of portrait photography takes on the role of a voyeur, particularly with images that expose the oppressed or marginalized. In real life situations the voyeur’s impolite stare is deemed socially unacceptable, but a face-to-face confrontation between the observer and the photographed sitter can evoke empathetic and emotional responses. The viewer may even begin to question personal responsibilities and accountability. In fact, the photograph itself may be more decisively unsettling than the concepts and arguments enveloping it.[1]

This exhibition investigates the expansive history of photographic portraiture from the University of Saskatchewan Art Collection. The Sitter follows the history of the medium from the daguerreotype to contemporary photo-conceptualism and digital manipulation.

[1] Martha Rosler, In, around , and afterthoughts on documentary photography

The daguerreotype was invented in 1839 by French Artist and chemist Louis J.M. Daguerre. This type of portraiture was primarily a memento that validated identity, and was an inexpensive way of historically documenting a family’s existence. Given the discomfort involved in sitting for the lengthy 30 second to 8 minute exposure times, often with a metal vice holding the head still, the facial expressions of the sitter are of resolute indifference.[2] As equipment became more advanced, photographers began to utilize their portrait studios and staged theatrical situations. This incorporation of the studio space began the transition from photographer to artist. The Parisian School of photography was notably one of the first to produce artist-photographers and playfully introduced costumes, props and sets for their subjects.[3]

As the photographer investigates their chosen subject, they often construct the environment they would like to convey. Artistic documentation (in contrast to photo journalism) becomes less factual when inherently manipulated by the artist. Brenda Pelkey compares private property and public identity in her theatrically lit photographs of domestic landscapes. The idiosyncratic sensibilities [in the photograph Front Yard Bavarian Village, Robert Wanka] challenge our definitions of monuments and of public art.[4] Thelma Pepper’s nursing home residence series attempts to document the “forgotten” elderly demographic. Pepper’s images individualize and sentimentalize her subjects, but also inherently document the unsettling fate of human decay.

The juxtaposition of artists Frank Pimental and Randy Burton exemplifies the diversities within North American social classes. Pimental photographs socially marginalized individuals in the gritty decay of 1980’s urban America, while Burton documents 1990’s upper-middle class Saskatonians in their utopian suburban homes. In both series, the sitter’s transcend a simple portrait and become a mechanism for the artist to transmit cultural messages about wealth, privilege, and diversity.

[1] Martha Rosler, In, around , and afterthoughts on documentary photography

[2] Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History, 2003

[3] http://www.e-flux.com/shows/views/6503

[4] Southern Alberta Art Gallery, Gallery, September/October/November, 1992