The Structurist (1960-2020)

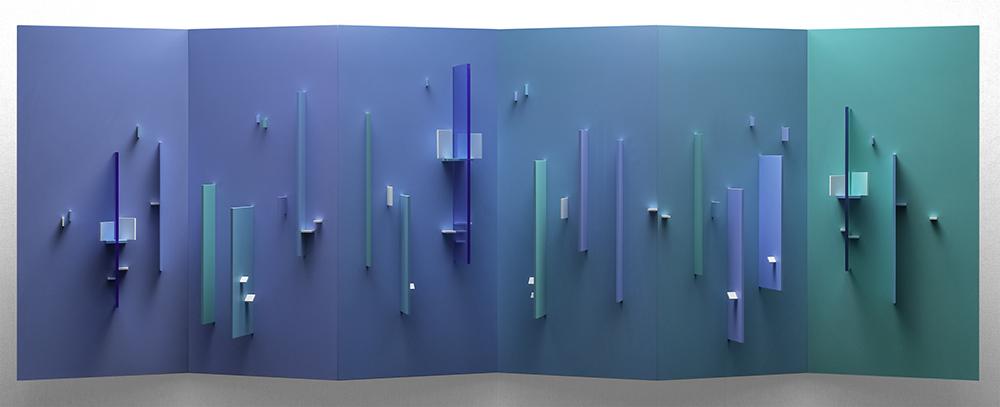

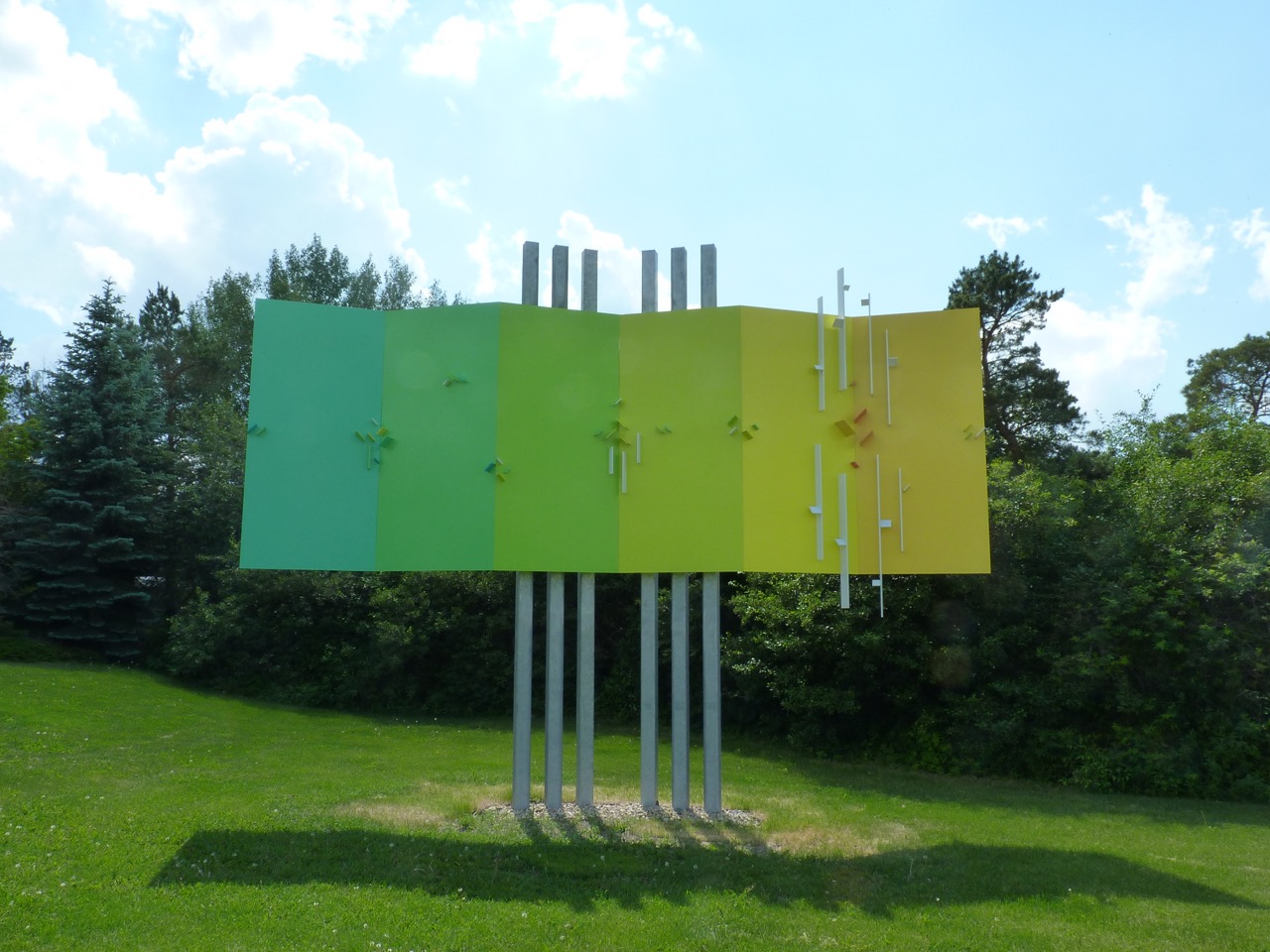

The Structurist was an international art journal founded in 1960 at the University of Saskatchewan by Eli Bornstein. Between 1960 and 2020, the journal published 52 issues primarily concerned with the building processes of creation in art, architecture, and nature. It focused on ideas in architecture and the arts – including painting, sculpture, design, photography, music, and literature – their histories and relationships to each other, as well as to science, technology, and nature. One ongoing interest was abstract constructive art and its origins, as well as the future development of media incorporating structure and color in space. Varied themes concentrated upon contemporary cultural problems and interdisciplinary subjects neglected by other art periodicals of the time. Notably, the journal published essays by leading artists and pedagogues such as György Kepes and Eli Bornstein; reprinted seminal texts by Frank Lloyd Wright, Piet Mondrian, and László Moholy-Nagy; and regularly featured Structurist artworks by Elizabeth Willmott and Charles Biederman, among others. For the duration of its publishing, The Structurist became increasingly concerned with the relationship between art and ecology; how art and architecture can participate in preserving and protecting our threatened ecosphere.

The Structurist began and continued as an annual publication until 1972 when it shifted to publishing biennially as double issues. Its distribution extended to over 30 countries and included in its standing subscribers many of the finest museums and university libraries in the world. It continues to be a valuable reference for research, scholarly, and creative work. Numerous books, articles, and theses have utilized or reprinted material originally published by The Structurist.

What's In a Name?

The following text comprised the opening salvo of each issue of The Structurist:

WHAT'S IN A NAME?

Semanticists tell us that our use of language is inseparable from the way we think and act. Words can reveal or blind, can level or erect walls, can open or close doors to perception and communication. They can be useful in identifying differences, but when words are misused or distorted, they lose their value. The meanings of words change and can have a wide variety of associations and implications. Reading and hearing, writing and speaking are subjective operations which allow for an infinity of distortions in projection and reception, so that communication is always a problem. In this sense, to use words is to live dangerously. But words can evoke new worlds of awareness, become more than mere sounds or signs, if the dangers are recognized and respected.

There is a scarcity of meaningful writing about contemporary art. The prevailing use of bewildering and pretentious language is undoubtedly symptomatic of the condition of art itself. The word art has been subject to recurring explosions of meaning since the turn of the last century. These fragmentations account for the increasing proliferation of new names of ever-new schools and fashions of art. The earlier "isms" such as Impressionism, Cubism, or Constructivism are popularly and grossly misrepresented and their limited value as historical labeling devices has in our time been badly abused. Cezanne said: "If they try to create a new school in my name, tell them they have never understood, never loved what I have done." The multitude and variety of art "isms" founded upon Cezanne have obviously ignored his words.

Names and labels may begin in all innocence as germinal ideas and as initial means of identification, and as such represent the beginnings of growth. But where these beginnings harden and "isms" emerge with self-appointed "leaders," partisan "creeds," and "disciples," we can anticipate the end of growth. Such "isms" usually produce intolerance and self-righteousness - dogmas for self-justification which become barriers to free and open inquiry. In our own time, with the many token "isms" in politics and art worn thin, we may hope to begin to bypass such obsolete terminology and the personality cults they fostered.

Over the last half century, the root word structure and its various derivatives have come increasingly into prominence in art. There remains considerable diversity of opinion as to its special meaning, application, and relevance. Nevertheless, various forms of the root word have appeared in numerous art movements for many decades. The word structure means to build, to construct, to form, as well as the organization or morphology of the elements involved in the process. It can be seen as the embodiment of creation. The quest for structure in art has been a quest not only for form but also for purpose, direction, and continuity.

The Structurist, founded in 1960, incorporates the root word structure in the word structurist. This is not meant in the sense of "ist" as a professional follower of some "ism," but as the Oxford definition suggests (see below) simply as "a builder." This is meant to suggest formative, organic, integrative ideas I principles I processes I approaches. The structurist artist as "a builder" is concerned with the building I growing processes of creation in Art and Nature. The Structurist does not adhere to or interpret any individual or "ism." It is interested neither in promoting personalities nor in fostering "schools" or "styles" of art. It is interested in a free exchange and exploration of a wide variety of ideas contributing to our growing knowledge of the process of creation in all fields relating to art.

The term 'Structurist Relief' was coined in the first issue of this publication only to differentiate between varieties of the abstract constructed relief, which has evolved over the past century as a new medium. For example, one particular concern was the vital element of color and its development in space, which was furthered by reproducing in color for the first time the newly termed Structurist Reliefs. However, the term is freely used and adopted by those sympathetic to some of these concerns. As a useful label, it is the sum total of many persons' conceptions of it and very much open to the continuous process of being defined, transformed, and developed by the commitments and contributions of many artists. This label-as most labels are destined to do- may eventually outlive its usefulness and be discarded. For it is only a convenience and used for the value of what's in a name.

| STRUERE STRUCTUS STRUCTURA STRUCTURE STRUCTURIST* STRUCTURAL STRUCTURALIST STRUCTURALISM STRUCT STRUCTIVE STRUCTION |

INSTRUCTOR DESTRUCT DESTRUCTIVE DESTRUCTION DESTRUCTOR OBSTRUCT OBSTRUCTIVE OBSTRUCTION OBSTRUCTOR CONSTRUCT CONSTRUCTIVE |

CONSTRUCTIVIST CONSTRUCTIVISM CONSTRUCTION CONSTRUCTIONIST CONSTRUCTIONISM CONSTRUCTOR SUBSTRUCT SUBSTRUCTURE SUPERSTRUCT SUPERSTRUCTURE etc. |

*Structurist

(f. STRUCTURE sb. + -IST)

A builder

1860 WORSCESTER (citing N. Brit Rev.)

As cited in OXFORD NEW ENGLISH DICTIONARY.

Online Journal

The Structurist can be accessed online through The University of Saskatchewan's library.

Complete Index (1960-2020)

A comprehensive index for The Structurist is available here.

Issues

- 1: Structurist Origins/Developments

- 2: Art In Architecture

- 3: Conflict/Creativity/Evolution in Art

- 4: Art and Music

- 5: Growth in Art and Nature

- 6: Art and Technology

- 7: Creation/Destruction

- 8: Light/Color/Space/Structure in Art and Nature

- 9: The Oblique in Art

- 10: Art and Morality

- 11: An Organic Art

- 12: Art, Language, and Literature

- 13/14: Light/Color

- 15/16: Time/Space

- 17/18: Art and Vision

- 19/20: Art as Truth/Art as Celebration

- 21/22: Art and Technology

- 23/24: Nature and Art

- 25/26: The Artist

- 27/28: Transparency and Reflection

- 29/30: Continuity and Connectedness

- 31/32: Structure and Color in Space

- 33/34: The Ecology of Creativity

- 35/36: From the Mechanical to the Organic

- 37/38: MEMORY & PROGRESS

- 39/40: Millennial Considerations of Art, Architecture, and Ecology

- 41/42: Art and Altruism: Aesthetics and Ethics

- 43/44: Toward and Ecological Ethos in Art and Architecture

- 45/46: Regenerating Art and Architecture in Nature’s Landscape

- 47/48: Art and Architecture in the Biological Century

- 49/50: Toward an Earth-Centered “Greening” of Art and Architecture

- 51/52: Evolution & Ecology in Art